One afternoon in Lagos, a man in a wheelchair arrived at a popular bank branch to collect money sent to him by his brother. The banking hall was busy, the air-conditioners were humming, and customers were being attended to. But the man could not enter. There was no ramp. Just a flight of stairs and a security guard who shrugged and said, “Oga, you have to find someone to carry you.” That moment captures a hard truth many Nigerians miss: disability in Nigeria is not just about health. It is about rights, dignity, and how society is organised.

Too often, we treat persons with disabilities as objects of pity, charity, or prayer points. We donate rice, clap for them during empowerment programmes, and move on. But under Nigerian law, disability is not a favour and not a burden. It is a rights issue. And it concerns every Nigerian, because disability is not a stranger. It can come through accident, illness, age, or even childbirth complications. The law recognises this reality, even if society sometimes pretends not to.

Under Nigerian law, a person with disability is not only someone who uses a wheelchair or a white cane. It includes people with physical impairments, visual challenges, hearing loss, speech difficulties, intellectual disabilities, mental health conditions, and long-term illnesses that affect daily living. Some disabilities are obvious. Others are invisible. A person may look “normal” but struggle with severe hearing loss, epilepsy, or mental health conditions. The law does not measure disability by appearance. It measures it by the barriers a person faces in functioning fully in society.

This is important because many Nigerians still carry harmful beliefs. Some think disability is punishment from God or the result of spiritual attacks. Others believe persons with disabilities are automatically dependent and incapable. The law rejects all of that. Disability is not shameful, and it is not weakness. It is a human condition that deserves respect and protection.

The foundation of disability rights in Nigeria starts with the 1999 Constitution. The Constitution guarantees the dignity of every human person and forbids discrimination on any ground. Although disability is not expressly listed in the discrimination clause, Nigerian courts and lawmakers have made it clear that denying a person equal treatment because of disability violates constitutional values of dignity, equality, and freedom.

One of the strongest demands of the law is accessibility. Accessibility simply means that public spaces and services must be designed in a way that persons with disabilities can use them without humiliation or dependence.

Building on this, Nigeria enacted the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act in 2018. This law is a turning point. For the first time, Nigeria said clearly and boldly that discrimination against persons with disabilities is illegal. Not immoral. Not unfair. Illegal. The law applies across the country, to government, private individuals, companies, schools, religious bodies, and anyone dealing with the public. It recognises that charity alone cannot fix discrimination. Only enforceable rights can.

Nigeria is also a signatory to international human rights agreements that protect persons with disabilities. These agreements reinforce the idea that disability rights are not special privileges. They are basic human rights that every civilised society must respect.

One of the strongest demands of the law is accessibility. Accessibility simply means that public spaces and services must be designed in a way that persons with disabilities can use them without humiliation or dependence. This includes buildings, roads, transport systems, schools, hospitals, offices, and even places of worship.

In practical terms, accessibility means ramps instead of only stairs, functional elevators, accessible toilets, clear signage, Braille materials, and sign language support where necessary. It means buses that can accommodate wheelchair users, hospitals where deaf patients can communicate effectively, and public offices that do not treat disability as an inconvenience.

The law gave a transition period for public buildings and facilities to comply. That period has expired. Non-compliance now attracts legal consequences. Yet, across Nigeria, many government offices, courts, banks, universities, and churches remain inaccessible. A wheelchair user cannot enter many courtrooms to seek justice. A visually impaired student struggles to access learning materials. These are not minor oversights. They are violations of the law.

Inclusion goes beyond physical access. It means equal participation in all areas of life. Children with disabilities have the right to education without discrimination. Schools cannot refuse admission simply because a child is deaf, autistic, or physically challenged. Employers cannot deny someone a job simply because of disability if the person is qualified and can perform the work with reasonable adjustments.

In the workplace, inclusion may mean flexible hours, assistive technology, or minor modifications. These are not acts of kindness. They are legal obligations. In politics, inclusion means accessible voting processes so that persons with disabilities can vote independently and secretly like every other citizen. In healthcare, it means respectful treatment and communication, not neglect or mockery.

Discrimination against persons with disabilities in Nigeria often hides in everyday behaviour. A landlord refusing to rent a room because “wheelchair go spoil the house.” An employer discarding an application without interview because of a hearing aid. A church seating persons with disabilities at the back “so they won’t disturb service.” A bus driver refusing a blind passenger because boarding will take time. These actions may look ordinary, but under the law, they are unlawful.

Discrimination can be direct, such as outright refusal, or indirect, such as setting conditions that unfairly exclude persons with disabilities. The law recognises both. It also provides penalties, including fines and possible imprisonment, for those who violate these protections.

The duty to protect disability rights does not rest on government alone. Federal, State, and Local Governments must ensure policies, infrastructure, and services are inclusive. Employers must create fair workplaces. School owners must design inclusive learning environments. Religious institutions must open their doors fully, not selectively. Landlords and property managers must rent and manage properties without discrimination. Saying “I didn’t know” is not a defence. The law expects everyone to know and comply.

When rights are violated, the law provides remedies. Persons with disabilities can report discrimination to the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities, a body created to monitor, enforce, and promote disability rights. Complaints can also be taken to court. Human rights organisations and legal aid providers can assist. Remedies may include compensation, court orders stopping the discrimination, and even criminal sanctions in serious cases. The law encourages calm, firm, and lawful assertion of rights, not silence or self-blame.

For the ordinary Nigerian, disability rights may seem like someone else’s problem. They are not. An inclusive society is safer, healthier, and more productive. Ramps help pregnant women and the elderly. Clear signage helps everyone. Respectful workplaces build stronger teams. And life has a way of humbling us. An accident, illness, or age can turn anyone into a person with disability overnight.

At its core, disability rights remind us of our shared humanity. They challenge us to build a society that does not discard people because they move differently, hear differently, or think differently. The law has spoken clearly. Persons with disabilities are not asking for sympathy. They are demanding justice.

Nigeria must move beyond token gestures and emotional speeches. We must change attitudes, demand accessible environments, and report discrimination when it happens. Disability rights are human rights. And how we treat the most vulnerable among us says everything about who we are as a nation.

READ ALSO:

Between personalities and principles: The institutional toll of the Ahmed-Dangote rift

Troops repel drone attack in Borno, rescue kidnap victim

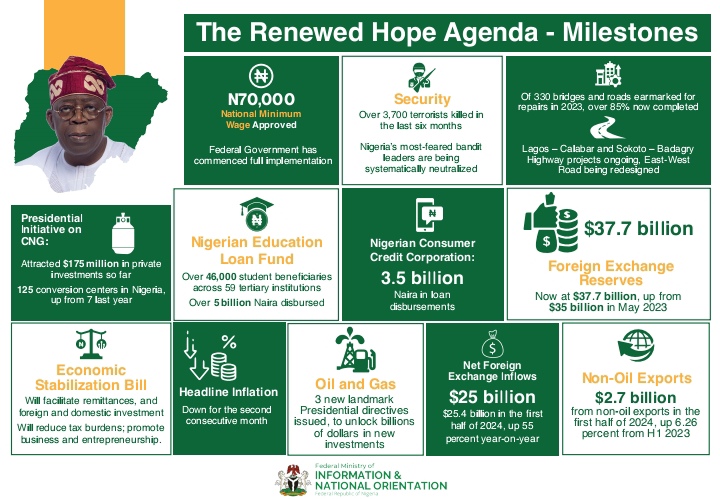

Tinubu to present 2026 Budget to NASS on Friday

Multiple explosions hit Auchi, police speak

Madam Ayodele Lawal: Family releases burial programme

JUST IN: Farouk Ahmed resigns as Tinubu nominates successor

Driver absconds as truck kills two, injures three in Lagos

Tinubu seeks Senate approval of 2024 Appropriation Repeal, Re-enactment Bill

APC chair, Yilwatda, reaffirms party stability drive as TPI emerges as ideological nerve centre

Thrifto: Nigeria’s digital platform for group savings goes public

BOOK REVIEW: Exploring the power of patience, resilience for ambition