A review of Yakubu Mohammed’s ‘Beyond Expectations’

My first love is literature; I love everything connected with language and its performances. But during my secondary school years, I was immersed in that eternal dialogue between mind and matter, finding ease and delight in Maths, Physics, and other science subjects. My path seemed clearly charted, guided by the logic of numbers and the certainties of experiment. Then, at some point, some big boys in Lagos started a news magazine called Newswatch and took the whole nation by storm. In their reports and commentaries, the reading public beheld excellence in its purest form. I read them: Dele Giwa, Dan Agbese, Ray Ekpu, and Yakubu Mohammed, and something within me began to stir. Chewing, swallowing, and digesting their words convinced my river to change course. It was time to face the arts and be like them. That decision became the granite foundation of my journalism story. To be asked to review the memoir of one of the gods of that journalism of excellence is, for me, an opportunity for my river to pour libations at its source, an honour most cherished.

For someone like me, who recently wrote and published a preview of this book, being asked to present a full review before such a distinguished audience as this, an audience that cuts across faiths, fields and fraternities, feels a bit like being asked to describe the sunrise again, but now beneath the gaze of the sun itself, while every star in the firmament sat in solemn witness. Still, this book, ‘Beyond Expectations’ demands another telling, because every reading reveals a new gleam in the gold of Yakubu Mohammed’s destiny.

As a student of literature, when I first saw the title of this memoir, what came to my mind was Charles Dickens’ classic, ‘Great Expectations’. And so, when I was summoned to come and be the reviewer here and now, I thought a journey into Dickens should resonate deeply with Yakubu Mohammed’s life story. And, truly ‘Great Expectations’ provides a philosophical doorway into ‘Beyond Expectations’. There are passages that tie the English classic’s reflections on destiny and moral integrity to the Nigerian memoir’s lived experience of resilience, faith, and character.

“Life is made of ever so many partings welded together,” Charles Dickens wrote in Great Expectations. It is his way of saying that destiny is not a straight line but a chain of separations, turns, and welds, the forging of one’s path through both loss and will. Reading Yakubu Mohammed’s Beyond Expectations, one senses that same truth unfolding in a different tongue and terrain: a life of many partings, disappointments, misses, close-shaves and redirections, all welded together by faith, grit, and an unbending moral spine.

A riveting story of four parts, 27 chapters, Yakubu Mohammed’s memoir begins, fittingly, with mystery: the author does not know the exact date of his birth. For a journalist whose craft depends on detail, this uncertainty feels poetic. In a world obsessed with records, he calmly chose April 4 as his birthday; a quiet act of rebellion and self-definition. Where others rely on documentation, he relied on destiny. He did it and says what he did calmly: “My uncle was not sure of the exact date in April. No matter, I took over from where he left off and decided, without any facts or figures, that it must be the fourth day of April, so April 4 became my birthday.” April 4 became not just a date for him, but a declaration: that life could still be authored by faith and will.

The author’s very first sentence in Beyond Expectations, is “I begin in the name of God Almighty,” (XXIII). Yakubu Mohammed transforms the story of his life into a spiritual odyssey shaped by faith, family, and providence. He recalls that his name, drawn from an Igala legend of persecution and survival, later linked to Dan Fodio’s Jihad in Northern Nigeria, carries a sacred weight, a sign of divine destiny that would mark his journey from birth. That destiny first revealed itself in tragedy narrowly averted: as an infant (less than a month old), he was rescued from a raging fire that consumed his family’s grass house and all his mother’s possessions. His mother, who lost all her clothes, reacted tearfully yet triumphantly.

Pointing at Yakubu with tears of joy flowing freely she said: “That is my cloth, my belonging, my all-in-all. I have not lost anything. Yakubu is my cloth, he is my God-given garment and that is enough for me”. (Page 5).

This declaration of maternal devotion sanctified Yakubu’s survival and set the tone for a life guided by divine protection. A few years later, another symbolic gesture deepened the themes and the spiritual narrative: in 1958, three days after enrolling in school, his unlettered father presented him with a pen (page XXIV). In Islamic teaching, the Pen was the first creation, commanded by Allah to write all things decreed until the final hour. To young Yakubu, it became a prophecy, a sign that his calling lay in the written word.

Through these tender recollections, Mohammed presents his life as a succession of events and as a drama of destiny, where faith (and fate) remould suffering into survival, where family serves as the vessel of divine grace, and where the pen, given in innocence, becomes the tool through which purpose is fulfilled. From that moment of fire to his rise as editor under Publisher M. K. O. Abiola, Beyond Expectations traces a journey of resilience and faith, a life that, as the title rightly affirms, blossomed far beyond human expectations.

Some words on the book’s form, language and style. Yakubu’s language is very accessible. The plot is linear. It starts with the author’s early life, moves in 106 pages to his life in the media which takes 184 pages. The remaining 102 pages are devoted to his public service record, his politics. The sentences are simple, the words clearly collocate with the sense and the context. Yakubu’s prose mirrors his personality: it is calm, pinpoint, precise, contemplative. He writes like a man who has learned that wisdom often lives in restraint and subtlety. The humour on his pages sparkles; it winks and blinks quietly like the lagoon; the insights arrive without fanfare like rain divorced from thunder. One minute he recounts the absurdities of human thoughtlessness with a wry, grimly mocking smile; the next, he meditates on fate with the calmness of faith. Through it all runs a steady stream of gratitude, a constant flow of appreciation; what he calls “the unseen but active hands of Allah (SWT)” guiding each turn of his story.

Yakubu got his first gift, a pen as a child.

But before the pen could meet its purpose, it would first write through pain. In one of the book’s most poignant chapters, Mohammed recalls how he was cheated twice in his quest for education. Those two early heartbreaks nearly derailed his future; they could not. Instead, they deepened his resolve.

The first came when he passed the entrance exam to the senior primary school at Ogane-Aji only to discover that his name had been crudely crossed out on the list of successful candidates and replaced with another pupil’s. Hear him: “When the results of the entrance examinations came, I was gripped by shock and disbelief. I did not fail; at least that was clearly shown on the typewritten list that was pasted on the school notice board. The shock, which threw me into an emotional tailspin, was that someone, somewhere had carefully crossed out my name on the list of successful candidates with a ballpoint pen and replaced it with the name of a female classmate. I could not comprehend the incongruity of it – they were saying, but who were the they’?- that I did not fail but I did not pass! It immediately dawned on me that my successful result had been annulled with a fiat…”(Page 19).

His teachers were helpless; they could do nothing to challenge the injustice.

The second disappointment was when he was denied admission into St. John’s College, Kaduna, despite excelling in the entrance exam, because he refused to renounce his faith. Some Reverend Fathers asked him if he would convert to Catholicism if admitted, his calm and honest answer was an unhesitant “No”. He was told:

“Here is a Catholic school and you are doing well even as a Muslim. Would you agree to convert to Catholicism if admitted to college.”

“I did not hesitate to answer. And my answer was an unequivocal No.”

That ‘No’ sealed his fate.

Yakubu Mohammed, was the only one who passed the written examination, but when the letter of admission came a few weeks later, it was not for him. The letter went to his classmate who did not pass (see page 27). If this happened today, it would be a counter-point to Donald Trump’s single narrative that religious persecution is a one-faith blight on the face of Nigeria.

Twice denied, yet undeterred. The boy who had been erased from one list and removed from another would soon pass the common entrance into a government college, where there was no gatekeeper; where merit itself was the front door’s key.

From his humble beginnings, Yakubu’s path would rise steadily. He passed his exams, went to UNILAG and with his pen made himself known. The story of his journalism exploits as an undergraduate is worth reading in this book. Where I come from, we say that cats that will grow to kill rats are always smart as kittens.

From classroom to newsroom, from editor’s desk to public office, Yakubu’s story is a journey powered by perseverance, the story of a life told in headlines and deadlines. Every page of this book testifies to that.

The author’s early struggles reveal the moral foundation of ‘Beyond Expectations’: that integrity is not an elective but a core course. The same child who refused to yield to injustice became the man who refused to trade truth for convenience. As a senior journalist with the New Nigerian, as the editor of National Concord, and later as Pro-Chancellor and chairman of council of two Federal Universities, (one of them the great ABU, Zaria), Mohammed consistently walked that thin, difficult line between service and survival, between principle and politics. He did so, suffered and moved on without bitterness.

The last part of the story is entitled ‘Politics’ (Page 339-389). Yakubu’s adventure in PDP and APC politics is a lesson for the motherless never to follow the initiate into the forest of the heartless. One of the chapters he christened ‘where angels fear to tread’. The second is ‘Cocktail of Mischief and Betrayal’. Sample: the APC announced in 2015 that he withdrew for Abubakar Audu. He did not withdraw but the party insisted he did.

Yakubu Mohammed complains loudly in this book that he suffered several arrests and detentions from the government and its agents. But it is always better to lose one’s cap than to lose one’s head. Hubert Ogunde sings in an album that a man that is beaten by the rains but escapes the withering celts of Sango should learn to thank God (eni òjò pa tí Sàngó ò pa, opé l’ó ye é). Mohammed is lucky that he lives to write his story. His friend, Dele Giwa, was not that lucky; he died before his time.

When a friend and colleague of Dele Giwa writes a book, a memoir, he is expected to answer or, at least, seek an answer to the question: Who Killed Dele Giwa? Does this book answer it? Giwa’s author-friend has ample space for an interrogation of that nagging question: Who killed Dele Giwa? He asks that question and raises posers which only he, Ray Ekpu and Dan Agbese could raise. Then he provides insights. Was Newswatch doing a story on a certain Gloria Okon? Who really was she? Yakubu’s book answers the questions in a manner that may activate many more people to write their own versions of the truth; some are reacting already.

I have read many accounts that seek to answer that Dele Giwa question. I have read Brigadier General Kunle Togun’s 195-page “Dele Giwa: The Unanswered Questions’ published in 2002. Journalist and lawyer, Richard Akinnola has written several materials on that unfortunate event. He has, in fact, reacted in writing to this book. Well, Mr Yakubu Mohammed has written his insider’s account, we look forward to Messrs Ray Ekpu and Dan Agbese and other Newswatch great men and women to write their own memoirs. Probably at the end of the whole interventions, an acceptable answer will be distilled to the question: Who killed Dele Giwa?

The book contains more on Nigeria and its chequered history. How did David Mark accurately predict in 1994 that Sani Abacha would spend five years in power and would attempt to contest a multi-party presidential election with only himself as candidate? Why did M. K.O. Abiola contest the 1993 election even after he had been told eight years earlier by Yakubu Mohammed who dreamt that he would one day successfully gun for the nation’s top job but would have the crown blown away by a storm at his crowning ceremony.

Through this author’s life, we glimpse a broader Nigeria: the growing pains of a postcolonial nation, the trials of its media, the ethical tests of public service. Yet, unlike many memoirs from men who carry ugly scars of life, Beyond Expectations oozes no scent of bitterness. Its tone is neither offensive nor defensive; it is a thanksgiving, a 440-page-long song of praise.

There are several MKO surprises that should extract gasps from the reader. Imagine Abiola as a reporter pursuing a story with his editor in the dead of the night.

As editor of Abiola’s National Concord, Yakubu Mohammed says “one night, I was going to meet a news contact in Surulere. He (Abiola) had an idea of the story I was pursuing and he inserted himself into the investigation team. He offered to accompany me. We took off from his residence in my car. Only three of us; he, in the passenger’s seat and I, in the driver’s seat with one security detail at the back seat. We did not return to Ikeja until about 4.00 the following morning, mission accomplished” (Page 168).

Accounts of several escapades like this make the book a thriller. Or how should I describe a scene that has billionaire Abiola stranded in a motor park one midnight in Benin? The money man finally got bailed out by the police and on the way to Lagos that night, Abiola entertained his boys in the police car with good music – a fork and a plate supplying the percussion.

Readers will confirm that a time there was in Nigeria when a newspaper financed a bank. It is difficult to believe but that is what I read in this book by Yakubu Mohammed. Hear the author: “Abiola’s initial contribution to the establishment of Habib Bank which he co-founded with his friend, Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, was paid from the Concord purse. I knew it because I signed the cheque”.” (Page 176).

As Concord journalists, Dele Giwa, Yakubu Mohammed and Ray Ekpu were famous for the unconventional work they did; they were even more famous for the flamboyance of their social life and engagements. They were brilliant, hardworking and rich.

Professor Olatunji Dare in the Foreword to this book drops a positive line on the “quiet elegance” of Yakubu’s wardrobe. But they lived big. A columnist with the rival New Nigerian newspaper based in Kaduna went with the pseudonym Candido, one day, called them “the Benzy journalists in Lagos who wear Gucci shoes.” A journalist, even if an editor, riding a Mercedes Benz in Nigeria of the early 1980s was a big deal. But Yakubu Mohammed does not think it should be a big deal. “Yes, we were riding Mercedes Benz cars, but we were not the first journalists or editors to do so. I don’t know about Gucci shoes but we were frequent visitors to New Bond Street and Oxford Street, the high-end shopping areas of London. If we were the envy of colleagues, it was thanks largely to (MKO) Abiola’s large-heartedness and the generous support of many other good friends.” (Page 199).

In the 1970s through early/mid 80s, the Lagos/Ibadan powerhouse of the Nigerian media had “The Three Musketeers.” That was the honorific tag hung on Messrs Felix Adenaike, Peter Ajayi and Olusegun Osoba who were at the helm of the Nigerian Tribune, Daily Times/Daily Sketch, and Nigerian Herald. One is dead, one is abroad, the third musketeer (Chief Osoba) is here, in this hall as chairman. They were the reigning big boys of that period. Then came the three “Benzy journalists” in imported, expensive shoes.

Beyond Expectations is also a book on business plan and execution (see pages 210 and 211). The process that birthed Newswatch, and how the brand was lost, are worth reading by all aspiring media entrepreneurs. But on this, something is missing in the book: How did the promoters of the magazine arrive at the name Newswatch? Who suggested it? I searched and could not find it in the book.

The media is a long-suffering entity. The same with its operatives. You will find Yakubu Mohammed’s ‘Beyond Expectations’ a book of tribulations, an account of a few ups and many downs. It is in there, how people of power use and dump journalists, and how journalists disgracefully undermine journalists for patronage, positions and privileges.

You also see and feel accounts of the journalist’s patriotic actions, many times unappreciated by the beneficiary-society. German playwright and novelist, Gustav Freytag, in 1854 published his famous play, ‘Die Jouralisten’ (The Journalists), a comedy in four acts. A voice in that play describes journalists as “worthless fellows, these gentlemen of the quill! Cowardly, malicious, deceitful in their irresponsibility” (Act 3, Scene 1).

At a point in the plot, one of the characters says “The whole world complains of him (the journalist), yet everyone would like to use him for his own benefit.” Yakubu experienced this many times and it is there in the book. His partner, Dan Agbese, puts this starkly in the Preface: “He expects no rewards and receives none. Some pay him back with the coins of ingratitude. That should make a lesser man bitter but not Yakubu. He takes it in his strides.”

At the beginning of this review, I said this is a story of miracles and survival. One more story:

In 2005, some assassins, point blank, rained bullets on him and his wife, yet, like Gbonka in the fire of Alaafin Sango, Yakubu and his wife, Rabi, “escaped unhurt” (page XXV). The episode illustrates the book’s dominant themes: providence, miraculous deliverance, and the sustaining power of grace. How did the bullets miss husband and wife? I searched for clues; I found none. The Igala mystery man did not disclose how those bullets lost their potency.

Competently written, elegantly printed, properly-indexed and illustrated with beautiful, meaningful photographs. Beyond Expectations is, in every sense, a Nigerian story, one forged in the binary of hope and disappointment, fine-tuned by faith, and polished by time. It leaves the reader with inspiration, admiration and breath-taking awe that the boy who once had no birth date would one day leave his mark on history in bold, indelible ink. Indeed, Asale ni Oja n tooro: the market settles in the evening.

Yakubu’s memoir opens with the name of God; it ends with words about his Creator and his religion, Islam (Page 389). By the time one closes the book, Dickens’ line returns with renewed clarity: “Life is made of ever so many partings welded together. One man is a blacksmith, one is a whitesmith, one is a goldsmith, and one is a coppersmith. Divisions among such must come, and must be met as they come.” Life, indeed, is made of many partings welded together, only that in Yakubu Mohammed’s case, each weld glows with grace. From the erased name on a school list to the enduring signature of a top-rate journalist, media entrepreneur and public administrator, the arc of his life is proof that destiny may divide, but character unites. This is, indeed, an account of a life that is beyond expectations.

Ladies and gentlemen, I thank you for listening.

*This review was read at the book’s presentation on Tuesday, November 4, 2025 at the NIIA, Victoria Island, Lagos.

READ ALSO:

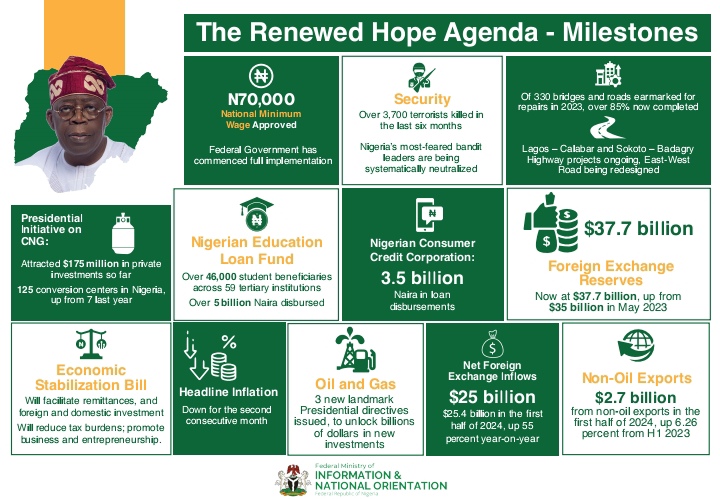

Tinubu to Nigerians: Don’t succumb to despair, we’ll defeat terrorism

What does America want from Nigeria?

UNILORIN alumni symposium holds on Saturday in Lagos

I-G withdraws fraud charge against Uba after refund of N400m

Police confirm arrest of two with human parts in Benue

Senate confirms Udeh for ministerial appointment