In Nigeria, we sometimes treat cheques as polite gestures or a way of saying, “Don’t worry, the money will come.” But the law does not share that sentiment. In the eyes of Nigerian law, a cheque is not a hopeful assurance. It is a firm representation that, as at the moment it is issued, sufficient funds exist in the account to honour it. When that representation turns out to be false, the consequences can move swiftly from embarrassment to prosecution.

The principal legislation governing this issue is the Dishonoured Cheques (Offences) Act, Cap D11, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004. Section 1 of that Act is clear and uncompromising. It provides that any person who issues a cheque for the payment of money which, when presented within a reasonable time, is dishonoured on the ground that there are insufficient funds in the account, or that the amount standing to the credit of the account is less than the amount of the cheque, commits an offence. The same provision applies where payment is stopped without lawful justification and the cheque is dishonoured. The law does not describe such conduct as a mere civil dispute. It describes it as a criminal offence.

The intention behind this law is straightforward. Commerce runs on trust. Markets function because people believe that financial instruments mean what they say. If cheques could be written casually, without funds to back them, commercial confidence would collapse. The Act therefore seeks to protect the integrity of financial transactions and to discourage the use of cheques as empty promises.

It is important for Nigerians to understand that the offence is anchored on the state of affairs at the time the cheque was issued. The common excuse, “I expected money to enter the account later,” offers no automatic protection. The law focuses on whether sufficient funds were available and whether the drawer had authority to issue the cheque when it was signed and delivered. Once the cheque is presented within a reasonable time and returned unpaid for lack of funds, the elements of the offence begin to crystallise. The burden may then shift to the issuer to establish a lawful defence, if any exists.

The consequences are not trivial. Under Section 1 of the Dishonoured Cheques (Offences) Act, a person convicted of the offence may be liable to imprisonment. The Act prescribes penalties which can include terms of imprisonment without the option of fine in certain circumstances, reflecting the seriousness with which the legislature views the matter. A conviction does not only carry the risk of loss of liberty; it carries the stigma of a criminal record, something that can affect employment, business credibility, and international travel.

The trouble, however, does not end with criminal liability. The same conduct can also give rise to civil proceedings. A bounced cheque does not extinguish the underlying debt. The payee is entitled to institute a civil action to recover the sum represented by the cheque, together with interest and costs where appropriate. The combined effect is that the issuer may find himself facing criminal prosecution on one hand and a civil lawsuit on the other. One act. Two fronts. Double exposure.

For those who receive a cheque that is dishonoured, silence is not wisdom.

Beyond the Dishonoured Cheques (Offences) Act, the Evidence Act 2011 also plays a role in such matters. Once a cheque is produced and dishonour is shown, certain presumptions may arise regarding consideration and regularity of the instrument, subject of course to rebuttal. The law does not leave the payee helpless. Documentary evidence from the bank indicating the reason for dishonour often becomes critical in both criminal and civil proceedings.

For the ordinary Nigerian, the trader in Onitsha, the contractor in Abuja, the landlord in Lagos, the businessman in Port Harcourt, the message is urgent and practical. Do not issue a cheque unless you are certain that cleared funds are available. Do not rely on anticipated inflows or verbal assurances. Do not assume that goodwill will cure legal defects. A cheque is not a gamble; it is a legal commitment backed by statutory consequences.

For those who receive a cheque that is dishonoured, silence is not wisdom. It is essential to obtain formal confirmation from the bank stating the reason for dishonour. The cheque must have been presented within a reasonable time, as contemplated by Section 1 of the Act. Prompt legal advice should be sought to determine the appropriate course of action, whether through a formal demand, civil recovery proceedings, or criminal complaint. Delay can complicate matters and weaken evidence.

In a country striving to strengthen its commercial culture and financial discipline, understanding the law on dishonoured cheques is part of civic education. A cheque may look like an ordinary piece of paper. But legally, it carries weight. It represents integrity, solvency, and credibility. When it bounces, it is not just money that falls; trust falls with it.

Nigerians must therefore learn to treat cheques with the seriousness the law demands. Financial responsibility is not merely a moral virtue; it is a legal obligation. And in matters of dishonoured cheques, the law does not joke.

READ ALSO:

Accident: 4-year-old boy, mother, others narrowly escape death

Explosion kills 33 miners in Plateau

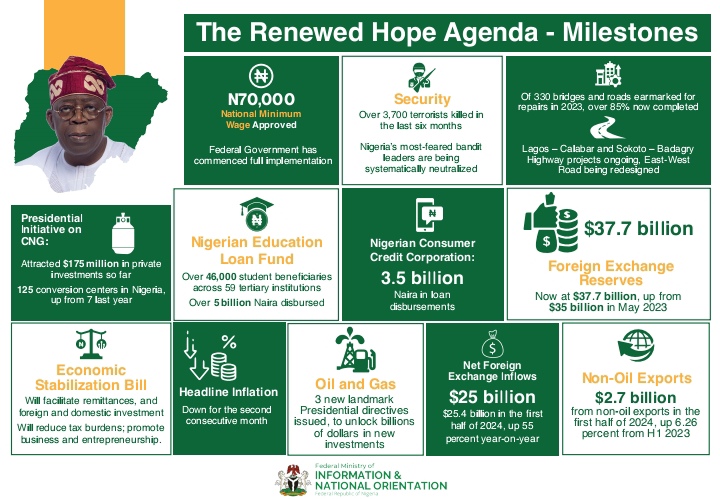

Tinubu signs executive order for direct remittance of oil, gas revenues to federation account

Tinubu signs amended Electoral Act 2026 into law

2026 UTME: No extension of registration deadline, JAMB warns

TRIBUTE: Desola: One year later, like yesterday, by Tunde Abatan