By AKIN OLANIYAN

The events of the last few weeks are a stark warning. They show what happens when our most private affairs – romantic betrayals and spiritual reckonings – are allowed to spill into the sprawling digital reality show, which social media has become blurring the line between private pain and public entertainment. I get the point about social media democratising communication, helping us to connect in a liberating way and, for many young Nigerians, a vital source of income within the attention economy. However, I find it difficult understanding what is entertaining when the commodity being traded is no longer just talent or comedy, but the raw, bleeding edges of human intimacy.

In what my generation will consider as a rude shock, the emerging pattern suggests that the courtroom for our relationships is no longer the in-laws residence but rather in the comment sections on social media, and the verdict now delivered in trending hashtags. In short, these two incidents offer us a distressing view into this new reality, driving a conversation that sits uncomfortably between gossip and a serious sociological crisis. On one hand, we have the chaotic implosion of the relationship between Gen Z TikTok stars, Peller and Jarvis. On the other, we have the scandalous fallout between a prominent social media cleric, Pastor Chris Okafor, and Nollywood actress, Doris Ogala.

The two cases differ in the demographics of the players – one pair represents the chaotic energy of the “Indomie generation,” while the other involves a mixture of religion and cinema. The immediate trigger for this cultural shift might seem like mere gossip, but the process bears a frightening resemblance to a public trial. Take the case of Peller and Jarvis. Their relationship was a classic study in what sociologists call dramaturgy – the meticulous performance of self on life’s stage. Their social media feeds were the ‘front stage’: a carefully curated stream of #CoupleGoals content, lavish gifts, and loved-up collaborations designed for an audience of millions. This was not just a romance; it was a joint venture; a brand built on performative intimacy. I bet they had no idea that this very archive of affection would one day be weaponised.

When the acrimonious breakup exploded online, it was a catastrophic backstage spill onto the front stage. Accusations of infidelity and financial exploitation were not whispered privately but broadcast on LIVE videos, their past content re-contextualised as evidence of deceit. Their followers, who had developed parasocial relationships with the couple – investing emotional energy in a one-sided connection – suddenly found themselves conscripted onto a jury. The conversation fractured into #TeamPeller and #TeamJarvis, with each side demanding “receipts” and delivering swift verdicts. The platform’s very design encouraged this tribalism; TikTok’s duet feature and Twitter’s quote-tweet function allowed the drama to be replicated, scaled, and sensationalised far beyond the original audience. The relationship, in its end, was treated as a corporate insolvency, with assets of reputation liquidated before a crowd.

Social media clout is seductive, working almost like a potent drug, and in the digital age, the courtroom is always open, and the audience is always hungry for the next case.

If the Peller-Jarvis saga was a messy corporate dissolution broadcast on TikTok, the case involving Pastor Chris Okafor and Doris Igala represents a more profound institutional challenge. Here, the clash was between two incompatible frames of reality. Pastor Okafor, like many spiritual figures, uses social media strategically – to majorly promote miracles, and solidify the ‘front stage’ image of the anointed ‘Man of God.’ His is a performance of anointing and authority. Doris Igala’s decision to ‘call him out’ on these same platforms was a seismic act. Her allegations of secret relationship and abandonment went beyond merely airing dirty laundry; to appropriating the power of social media to challenge what is supposed to be a traditionally unimpeachable source of spiritual authority.

Unsurprisingly, what followed typically confirms some things we know of the social media crowd. First, look at the cynicism. When Peller crashed his car, the immediate reaction from many was not concern, but doubt. “Is it a skit?” Is there just a hint here that we have become so used to scripted reality that we miss the real thing when we see it? Second, consider the transaction. In the Pastor Chris saga, comments often split along gender lines, but a recurring theme is the transactional nature of the relationship. Critics shame the woman for “dating a pastor,” implicitly suggesting that she should have known the rules of the game.

The discourse fragmented into a moral panic, where the personal became a societal parable about megachurch opacity and the vulnerability of women. The platform vernacular of Instagram—where a lengthy, emotional caption can be shared to a Stories archive—became her pulpit, while the pastor’s defence relied on the more formal, established authority of his church and legal statements. It mattered little where the truth ultimately lay; the act itself reconfigures the landscape of accountability, suggesting that when other channels feel blocked, the court of public opinion is permanently in session.

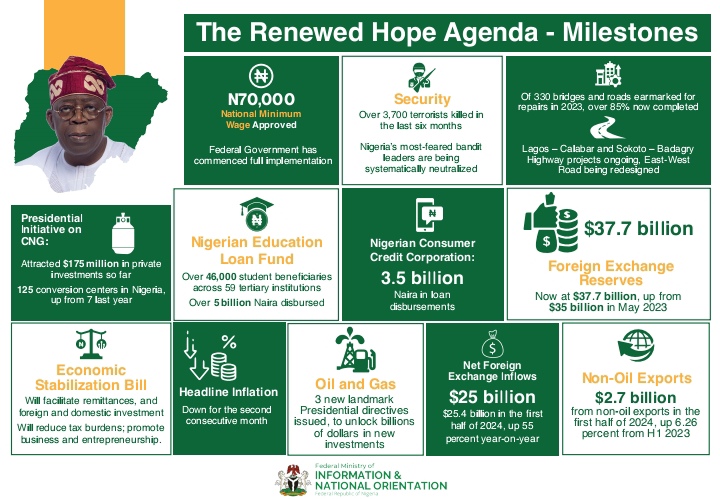

This impulse towards public tribunal is not limited to relationships. We see it in our political culture, where social media serves as the great leveller and amplifier of public sentiment as laid bare in the case involving Wike and the young soldier. The mob’s reaction was so terrifyingly swift, emotionally satisfying, and often devoid of nuance similar to the public shaming of Peller or Pastor Chris: a visceral, collective way to release pent-up tension through likes, shares, and savage memes.

So, here is the deep concern I have. These episodes are not isolated scandals but symptoms of living life on a public stage. We are encouraged, by the very architecture of these platforms, to perform our lives. For the influencer, intimacy is a metric. For the pastor, faith is a broadcast. And when these performances crack, the audience, now invested as both fan and judge, demands a spectacle. The lines between a private sorrow and public content have been obliterated, giving us a ring-side view of the commodification of conflict where personal strife has engagement value, and the incentive structure rewards escalation over resolution.

The psychology behind this is worth examining. Why would anyone choose this path? For influencers like Peller and Jarvis, the motivation is tied to the economy of attention; their livelihood depends on relevance, even if it’s fuelled by conflict. For someone like Doris Igala, it may be a desperate lever for a voice, a way to be heard when all other channels seem stacked against her. But scratch beneath the surface, and you might find signs of deeper issues that social media exacerbates – a need for validation so profound that even negative attention is preferable to silence, or an anxious attachment that mistakes public performance for genuine connection. In a culture where we ‘play too much,’ the line between serious testimony and sensationalist content can blur, with tragic consequences.

The danger, as with any mob justice, is that these digital tribunals are easily hijacked. They can be weaponised for personal vendettas, manipulated by bad actors, or simply become entertainment that consumes human dignity. One of the downsides to social media is the potential to digitally destroy people on the strength of allegations alone; and the unique persistence and searchability of digital content means the evidence never disappears means the trial can be re-opened at any time. The result: No chance of private forgiveness or reconciliation.

Trust rugged Nigerians, we will adapt. Content creators will mine the drama for skits and hot takes, growing their own followers from the rubble of another’s relationship. The cycle will continue because the platforms profit from our engagement, whether it’s inspired by love, faith, or hate.

So, what do I think about this new era of public relationships and digital reckoning? One, we are seeing the inevitable consequence of converting our private lives into scrollable feeds. Two, those foolish enough to be sucked into that undefined space are both perpetrators and victims of a system they did not create but now must survive. Third, some parts of the human experience – love, faith, betrayal, and redemption – require shadows, nuance, and a sacred privacy to ever truly heal, they should be kept away from social media.

Will they listen? I doubt. Social media clout is seductive, working almost like a potent drug, and in the digital age, the courtroom is always open, and the audience is always hungry for the next case.

*Dr. Olaniyan, the Convener, Centre for Social Media Research, Nigeria writes about digital culture

READ ALSO:

Dangote and the shady fuel sector, By Kazeem Akintunde

I’ll champion media freedom, engage other agencies -DSS DG

AFCON 2025: Morocco edge Comoros 2-0 in Rabat

Sanwo-Olu receives Opambata as activities for Eyo festival kick off

U.S. signs $5.1bn bilateral healthcare cooperation with Nigeria

JUST IN: 130 pupils of St Mary’s Catholic school released

Tinubu congratulates DSS DG, Ajayi, on IPI press freedom award

ICPC invites Dangote over petition against ex-NMDPRA boss

Man caught with 1,020 pills of tramadol, tapentadol at airport

Female drug kingpin arrested in Lagos with 23.50kg cocaine

Lagos housewife allegedly fakes own kidnap, extorts N2.5m from husband